A study has shown that nearly 1 in 5 school-age children in Africa have a fungal infection of the scalp referred to as tinea capitis with a reported 138 million cases of the infection found among school-age children in Africa, in the first African estimate of this disease.

The investigative team led by Dr Felix Bongomin and his colleagues from Uganda and Nigeria conducted a robust systematic review combining a total 40 studies from 17 countries across Africa reporting the prevalence of tinea capitis in a total of over 229,000 school-age children. The prevalence of tinea capitis ranged between 0.003% and 81% with a pooled prevalence of 23%. Bongomin et al. Tinea Capitis in African Children, Mycoses 2020.

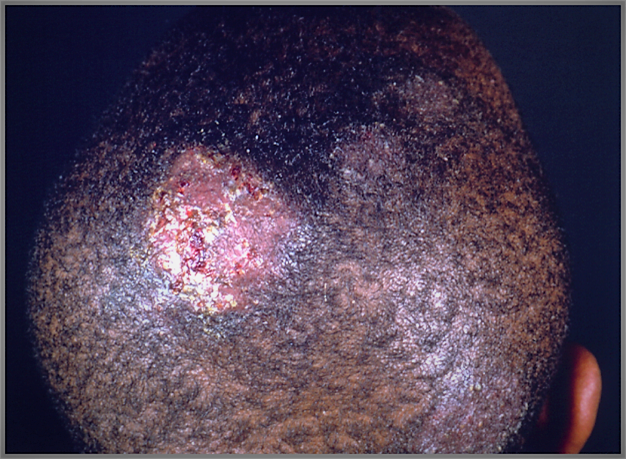

Tinea capitis is caused by fungi that can spread from humans to humans or animals to humans. Primarily found in children, some may suffer additionally from severe scalp infections known as kerion which is painful and can result in a permanent hair loss.

Dr Bongomin, who is a lecturer in Medical Microbiology at Gulu University Medical School, Uganda, and Ambassador for the Geneva-based Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections (GAFFI) said,

“In Africa, we are blessed with many children, who unfortunately because of many factors such as poverty, sharing fomites such as hair combs and beddings, sharing housing with animals, overcrowding and refugee status are at increased risk of acquiring this condition”.

He added,

“Majority of these children are in primary schools between the age of 5 and 15 years. These children suffer serious social stigmatization because of the visible hair loss and scaling on their scalp”

Dr Joseph Baruch Baluku and infectious disease physician from Mildmay, Uganda continued,

“Considering that the children at risk are from disadvantaged communities, the scalp infection is an unfortunate public testimony of this disadvantage. The psychological impact disease is likely to affect their self-image, and perhaps even academic performance”.

Tinea capitis is under-reported and neglected at all levels across the world. As noted in the study, only in 17 of 54 countries had any prevalence data of this disease published.

Mr Richard Kwizera who is the head of the Translational Research Laboratory at the Infectious Diseases Institute, Makerere University, Uganda spoke of possible reasons for this neglect, saying,

“The limited or under-reporting of a condition with such a high burden in our African setting is attributed to various factors such as; the non-painful nature of the disease, lack of diagnostic capabilities, high cost of treatment incurred by patient and utility of alternative African medicine/remedies”,

He added that,

“It is in fact considered both endemic and neglected in Africa, and most patients never seek medical care.”

Despite under-reporting and apathy towards tinea capitis, documentation of its adverse effects on school-age children has been around for years.

Tinea capitis was observed by skin experts Robert Willans and Samuel Plumbe in the 18th and 19th centuries, who concluded that, when left unchecked, the disease led to the closing of schools and significant periods of education missed by children forced to stay home, “The consequence of this is, to the unfortunate child, a loss of time at that period of life when it can be least afforded, the period of early education.” [1]

Perhaps the most well documented and more recent example of the mismanagement of tinea capitis treatment can be found within the historical reporting of the “Ringworm Affair” in which an alleged 20,000 to 200,000 Jewish individuals who were treated between 1948 and 1960 for tinea capitis (ringworm) with ionizing radiation to the head and neck area within Israel.

This led to cancerous and non-cancerous growths on many young patients and is considered one of the most salient examples of injustices that immigrants to Israel encountered in the 1950s as a result of shortcomings, negligence, paternalism, or irresponsibility.

References

1. Plumbe, S., An Address to the Governors of Christ’s Hospital, on the Causes and Means of Prevention of Ring-Worm in That Establishment; To Which Is Attached, a Few Rules for the Domestic Management of the Scholars during Their Vacations, London, 1834.

Referenced by Homei A & Warboys M. Fungal Disease in Britain and the United States 1850-2000. Science, Technology and Medicine in Modern History 2013 P18. ISBN 978-1-137-37702-9.